Well, well – look what I found today!

Ghost Ships Down Under

|

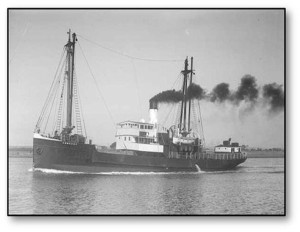

| TSS Coramba |

Here’s the text of the article.

Ghost ships down under

17 July 2011 Words: John Burke

Ballinteer-born Terry Cantwell was at a barbecue in a neighbour’s house near his adopted home on the state of Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula when a chat about shipwrecks over a few beers changed his life and his career forever. That conversation led him to spend the next four years charting the discoveries of a group of Australian shipwreck hunters.

The 47-year-old former teacher has just been commissioned by one of Australia’s largest TV production companies to film a six-part documentary series which will tell the island nation’s story of disaster at sea. Cantwell worked as a print reporter and radio producer in Melbourne before the closure of the radio station, when he diverted into teaching English. But the Irishman continued to contribute freelance articles to a local newspaper in the Victoria area.

Cantwell’s neighbour, Martin Tozer, a keen amateur diver and underwater explorer, mentioned that evening in 2007 that Cantwell might be interested in writing a story about a recent ship he and his friends had discovered. Tozer was part of a diving team founded by Mark Ryan, another Mornington local and descendant of Tipperary emigrants who had embarked on a mission to locate missing shipwrecks off Victoria’s coast. The Bass Strait is at the southern tip of Victoria and its notorious storms, hidden reefs and unpredictable weather made a dangerous passageway for the many trading vessels which used this route in and out of Melbourne from the 1800s onwards. Calling themselves Southern Ocean Exploration (SOE), the crew of a dozen divers were initially reluctant when Cantwell suggested that he document their undersea search.

‘‘They had been burnt before when a TV documentary crew spent some time with them, but nothing had come of it,’’ Cantwell says. The crew’s most recent discovery – a ship with strong Irish connections which sank 76 years ago claiming 17 lives – has already proved a big hit in the Australian media. The loss of the 50-metre TSS Coramba’s crew was a devastating blow to Depression-era Victoria when it sank in bad weather in 1934. Scores of divers had spent the past half-century searching for its remains with no success.

The wreck’s location had gone down as one of the greatest mysteries of Australian maritime history until SOE researcher Peter Taylor had a ‘‘hunch’’, as Cantwell calls it, about a possible search zone. The find, like many of SOE’s discoveries, has meant a lot to the families of those who died, many of whom have strong Irish links. For example, Jan Roberts’ grandfather died on the Coramba.

‘‘John Loring Sullivan was my paternal grandfather,’’ Roberts told The Sunday Business Post. ‘‘He drowned 19 years before I was born, so I never knew him. However, the story of the Coramba was part of my childhood and always fascinated me. ‘‘My brother is named after our grandfather – he is also John Loring. I had known through my brother for some time that divers were trying to find the Coramba. It was very special therefore when the wreck was located. I’ve always thought of the Coramba as ‘our’ ship and to think that people not connected to it would go to so much effort to locate it was wonderful.” Roberts, a family historian, says records suggest that her great-great grandfather was a convict transported from Fermoy, Co Cork, around 1818.

Audrey O’Callaghan, now aged 88, is another relative moved by the discovery, and she still remembers the last time she saw her father, John Dowling, the captain of the Coramba. She was 12 when she walked her 47-yearold father to the bus stop near their home in Williamstown before he set off on one last journey on the cargo steamer on a return trip to Warrnambool in the state’s southwest to collect goods.

‘‘We were very close . . . I kissed him good-bye and I said: ‘Dad, I wish you were at home every night like other dads.’He said: ‘I won’t be long’,” she told a local newspaper after the find.

Cantwell says the interest in the ship’s discovery is part of a newfound fascination among Australians in the history of their continent which they had ignored for years. ‘‘The history thing in Australia is very interesting,” he says. ‘‘They have really only discovered an interest in that side of things here for the past ten or 15 years. Before that, there was a lot of shame over the convict origins of the population, but there’s been a big swing towards people taking an interest in their history. This is a very maritime nation; just look at a map of Australia and you see that it’s all coastal development. The interior is really empty, so the sea plays a big part in Australian history.” Strangely, the Coramba tragedy was all but overlooked when it first happened.

‘‘More people died on the mainland that day in the ensuing floods, and the news of people being electrocuted by fallen power lines was more pressing than the disappearance of a coastal trader,’’Cantwell says. ‘‘Yet the Coramba was to become one of southern Australia’s most intriguing maritime mysteries.” The search for the Coramba was made more dramatic because of the discovery in 1987 by a fisherman of one of the world’s largest great white sharks in the area where the ship was believed to have sunk.

‘‘The idea of a seven-metre man-eater made many divers wary about diving in these waters,” says Cantwell. Undeterred, SOE searched for the Coramba for eight years in total,with Cantwell at their side for the past four years filming their every move. They found the steamer on May 29 this year, almost 20 miles from where most other divers had searched in what were dangerous ocean-going conditions.

‘‘We were also hit by a rogue wave that day that rolled the boat 60 degrees,’’Cantwell says. The find also meant a lot to Des Williams, author of a book on the tragedy called Coramba: The Ship The Sea Swallowed. He accompanied the SOE team on the day they discovered the vessel, all of which Cantwell has on film. ‘‘The discovery of the wreck of the Coramba for me is a fantastic event, a real ‘life moment’,’’Williams says. ‘‘After almost 30 years of following the story, researching it, writing a book about the wreck for the 50th anniversary of its sinking and having a close rapport with many of the relatives of the lost crew, it is a huge relief for all of us.”

Cantwell says he always had an interest in journalism, but didn’t imagine it would lead to him devoting several years to a single project under the sea. He left Ireland in 1986 at the age of 22 and ended up in Australia. ‘‘There wasn’t much happening in Ireland those days,” he says. After arriving in Australia, he decided to try his hand at journalism and looked for work as a freelance reporter with a local Melbourne newspaper, although he had no media experience.

He went through a number of jobs in print before finally settling in broadcasting. After his stint in the local Melbourne press, he saw an advertisement for what seemed an interesting job as a military reporter for the Australian Army Reserve force and went for it. ‘‘It involved mostly going on their golfing outings and writing about how good the officers were at golf,’’Cantwell says in his slow, droll accent which is a strange hybrid of Irish and Australian.

Eventually he became an established producer for a local commercial Melbourne radio station. ‘‘Something quite like Newstalk at home,” he says. He combined study with work, earning a degree in journalism at Deacon (sic) University before completing a Masters degree at Melbourne University. He also met and married his wife Caitriona, a native of Gorey, Co Wexford. Australians struggle badly to pronounce her forename, he jokes.The couple have two daughters, aged 15 and 21. The couple’s elder daughter is studying media. Journalism has not been plain sailing for Cantwell. After nearly a decade in radio which saw him end up as a producer on morning talk radio, the station closed and Cantwell was forced into a career re-think.

He went into teaching, ending up giving lessons in English and editing at a secondary school. However, he never left journalism far behind and had continued to do freelance work in both broadcast and print. It was then, when he least expected it, that his chance chat with Tozer at the barbecue changed his career path once again. After speaking to the SOE crew, Cantwell mentioned the shipwreck story to a friend, David Muir, who works with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Channel 7, known in Ireland for producing day-time dramas such as A Country Practice.

The pair put their heads together to consider a format for the documentary which they hoped to make. In the meantime, they formed a production company, Whitewater Documentaries, of which Cantwell is series producer and writer and Muir technical producer.

At the time, there was a local TV programme which aired in Melbourne called Australian Story, and Muir and Cantwell figured that they could shoot and edit a 30 minute documentary which would air on the programme. ‘‘That was our initial ambition,’’Cantwell says. But the story became bigger than their ambition, as the SOE crew’s success in discovering sunken ships grew.

Most of the SOE divers live around the Mornington Peninsula area and know it and its history intimately. The peninsula is a jut of land between Port Philip and Western Port that fronts an area of treacherous water covering a 200 square kilometre area. All have a keen awareness of how dangerous the waters are in which they carry out their explorations. South of the peninsula is the Bass Strait,which is significant in Australian maritime history for several reasons.

In practical terms, the only way for cargo to be shipped in and out of Melbourne was along the southern coastline via the Bass Strait. One of the main entry points for vessels into the city was Port Philip, which lies to the west of the peninsula. A number of key trading routes intersected the stretch of water south of the peninsula. These passageways earned a reputation as being too rough for the type of flimsy cargo vessels which frequently passed through it on routes between Sydney and Melbourne or from Melbourne towards Adelaide.

‘‘A lot of ships entering Melbourne got broken up and ended up on the floor of the ocean there,” says Cantwell. In the middle of the Bass Strait is the aptly-named Ships’ Graveyard, a 40 square kilometre zone where most of the estimated 800 ships which have sunk off the Melbourne coast since the late 1800s are believed to be interred in the murky depths below. There are two reasons why the peninsula is so littered with shipwrecks: the volatile weather conditions and the poor quality of the boats which sailed here.

‘‘The Bass Strait is the area of water between Tasmania and Victoria and it’s the notoriously rough sea that goes around the peninsula,’’Cantwell says. ‘‘There’s really nothing between the Bass Strait and Antarctica to break up the rough weather fronts which come all the way up from the south. The storms that build up from down there can really mess a boat up.” Hidden rocks and reefs, strong currents and unpredictable weather fronts all contribute to making the coastal passageways along the Bass Strait a high-risk route for cargo ships.

‘‘You can spend a day out there in the strait and it can be as calm as possible and then without warning it can turn into a maelstrom,’’Cantwell says. Critically, many of the wooden-hulled boats which sailed along the Victoria coastline during the 1800s and early 1900s were not fit for purpose, according to Cantwell. ‘‘A good many were called ‘coastal traders’, boats bought to do the trip from Sydney to Melbourne or into Melbourne from the Adelaide side,” he says. ‘‘They were never up to the standard of being able to deal with hard seas and in some cases they were probably overloaded.”

Of the 800 or so shipwrecks littering the seabed off the Victoria coast, just 200 are believed to have been located. ‘‘There are another 600 ships down there somewhere,” he says. ‘‘But these guys are the only ones who are actively seeking out these discoveries. There’s good reason why nobody else is doing it.”

It is expensive, time-consuming and can be dangerous at the most extreme depths of 90 metres or more. ‘‘The fact that nobody else is doing this is what got me interested in SOE’s work in the first place,” says Cantwell. When SOE takes to the water there are usually 15 or 16 people, between the actual divers, maritime researchers and Cantwell’s documentary crew.

The SOE team come from diverse backgrounds. Some of the men, like co-founder Mark Ryan, are commercial divers. Ryan is also a diving instructor and runs a diving shop. Others, such as senior SOE team member Martin Tozer, work in business, while Peter Taylor, who conducts most of SOE’s research, is a stonemason by trade. Many are also private boat owners and all were originally divers who came together because of a common interest. None makes any money from the explorations.

The search for the Coramba has cost the crew an estimated AUD$30,000 since they first began searching for the vessel in 2003. ‘‘They all contribute financially,’’Cantwell says. ‘‘It all comes out of their own pockets. If there are 15 or 16 blokes on a particular day, each man will contribute $50 dollars for fuel. After that, each man has got to spend about $100 on air for his own tanks. ‘‘And the water around here is particularly cold, so that means that you’ll probably need a dry suit to dive, as opposed to a wet suit. A dry suit can set you back $3,000. It’s a lot of money when you put it all together.” Not only is there no money to be made from their discoveries, but the divers could be jailed if they try to remove any of the artefacts which they uncover from a shipwreck.

‘‘Under Australian law you cannot take a single item from a maritime discovery,” Cantwell says, adding that the law allows a five-year jail term for anyone found to have pillaged a maritime discovery. ‘‘The find automatically becomes a heritage site and is treated like a grave site.” The Dubliner says their worst experience to date has been finding out that one of the ships they had located was subsequently pillaged by undersea divers.

‘‘It is something of a bugbear with Mark and Martin that once you find a ship, you have to declare it and you have to give out its coordinates,” he says. Cantwell says that before he got involved with the divers he had an expectation that they were essentially treasure hunters in search of underwater bounty. He says the reality could not have been further from this. Most of the SOE members are either keen amateur marine archaeologists or have a deep interest in maritime history.

Cantwell and Muir brought the idea of a one-hour documentary about SOE’s biggest discoveries to Bob Campbell at Screentime, one of Australia’s biggest and most successful TV production companies. ‘‘Bob came straight back and said he liked it a lot, but he said: ‘I can’t make money off a one-hour doco: I’ll need about six hours’,” Cantwell says. ‘‘We went back to the drawing board and thought about it and out of that we created the ‘Ghost Divers’ concept.” Each episode will focus on a separate SOE discovery and will begin by telling the story of the ship and the crew who populated it on its final voyage.

Cantwell had the idea of also using actors to recreate some of the drama of the sinking, but Campbell came up with a brainwave: to create a 3D diagram of the boat using old maritime plans and to show the sinking using CGI. Each story will also focus on a living relative’s journey to have their ancestor’s tragedy recognised. ‘‘It has been an incredible ride: a blur of shipwrecks, bad seas, diving, being continually wet, some big nights and great camaraderie,” Cantwell says.

The Irishman says ‘‘never say never’’ when asked if he and his family would ever move back to Ireland, but goes on to say that Australia has been good to them. Speaking to Cantwell, it seems the line between documentary-maker and explorer has become blurred over four years of diving with the crew. Speaking about the constant improvements the SOE team have made to their technique, he says that ‘‘we’’ are now using a former World War II PT boat for ‘‘our searches’’. It will allow the SOE team to travel further into the Southern Ocean. The ship, which is owned by another Irish sounding SOE member, Justin McCarthy, also has the distinction of having transported Queen Elizabeth II across Sydney Harbour in 1953.

Whatever fame or recognition the film series will bring to the SOE divers, their focus is on the work ahead.The team is currently searching for ten other wrecks. Included in the list are the Sappho, an anti-slaving admiralty ship that sank in the 1840s with 143 lives lost; the Federal,which disappeared without trace in 1900, and Cantwell’s own favourite, the Pingara, which disappeared near the Coramba with 31 lives lost -17 of whom were Chinese labourers. With 600 sunken ships still languishing on the sea floor off the rugged Australian coast, it would seem there is more than one series of Ghost Divers in the Irishman’s future.

This story appeared in the printed version of the Sunday Business Post Sunday, July 17, 2011

No comments:

Post a Comment